[This is a slightly tweaked cross-post from SignificantObjects.com.]

Here’s yet another twist on adding an invented narrative to a seemingly low-value thingamabob:

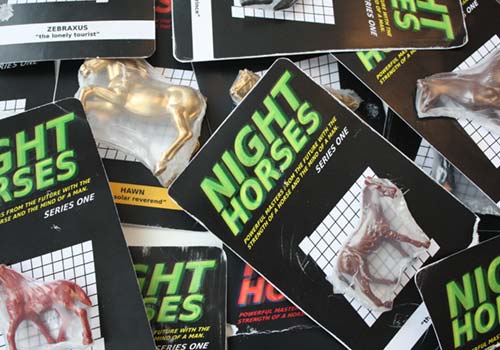

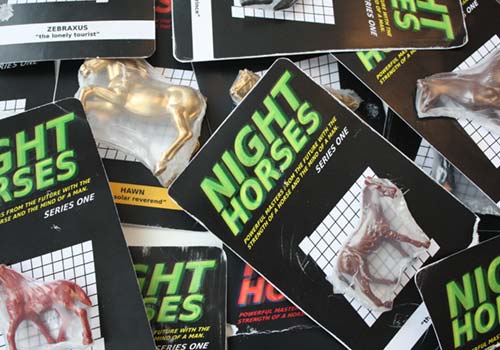

Designer Matt Brown bought a pack of 15 plastic horses for a couple of bucks. Then he dreamed up a name for each one, then packaging, reconceptualizing his two-dollar purchase as a line of toys, Night Horses, that were introduced in the late 1980s, and flopped.

Hey, remember Night Horses? (No, you don't.)

I love it!

More recently Brown has embarked on another project, turning some toy cars into another failed product line. They’ll be retroactively rebranded as Throttle Dukes. More here.

Throttle Dukes, to be.

Is this more evidence of the “significant objects meme” that my Significant Objects colleague Joshua Glenn has detected? I don’t know.

“I like taking things that are basically worthless and neglected and turning them into something that people could enjoy again,” Brown writes. Combine that with my longstanding interest in imaginary brands, and you can see why I’m so into it.

(Via Metafilter, where Brown was referred to as a “design fiction enthusiast.”)

I’m interested in this upcoming Frontline installment, Digital Nation, partly because the correspondent is Douglas Rushkoff. I started a while back to write a post here about his most recent book, Life Inc.: How the World Became a Corporation and How to Take It Back , but for various reasons never completed that, and I guess never will. So I’ll just give you the short version: I read it some months back and found it quite interesting and certainly provocative. I’m not really that well-read on Rushkoff’s work, but based on what I (thought I) knew, it was not what I was expecting.

, but for various reasons never completed that, and I guess never will. So I’ll just give you the short version: I read it some months back and found it quite interesting and certainly provocative. I’m not really that well-read on Rushkoff’s work, but based on what I (thought I) knew, it was not what I was expecting.

And while the book seems to have done well, I’m surprised it didn’t generate more mainstream discussion and reaction. That’s too bad because there’s a lot to discuss and react to. The most interesting aspect of it to me was the underlying argument that history since, say, the 1600s is not just a march of progress, but rather has also entailed some extremely significant losses along the way. I read this between reading Margaret Atwood’s Debt, and Lewis Hyde’s The Gift, so it hit on lots of things that have interested me lately. I even started listening on occasion to Rushkoff’s show on WFMU, Media Squat (now on hiatus) and that included some interesting discussions, notably the episode with Howard Bloom. But since most of his guests kind of see the world the same way he does, I still end up feeling a little frustrated — phrases like “bottom up” and “create real value” get tossed around a lot as if their meaning was obvious, and not contestable. It would have been useful if the book had attracted reaction from a broader range of sources, because I have a feeling that would have been provocative, too.

Anyway so it’s because of all this that I’m interested in Digital Nation — which I think under normal circumstances is something I would have shrugged off as likely-to-be-predictable. I’m curious of the ideas he seemed to be wrestling with in Life Inc. will manifest here.

On a possibly related note — related to digital life, anyway — Mind Hacks notes two bits of research of note: BPS Research Digest summarizes a study looking into how people with certain offline personality traits behave online. (Best line: “Students who scored high on psychoticism were also likely to say that they found it easier to reveal their true selves online than face-to-face.” Hmm, great.) And this earlier study finding consistency between online and offline social behavior. Maybe that all sounds sort of obvious, but keep it mind when you hear gurus generalize about social-Webness affects “everybody.”

Posted Under:

"Social" studies

This post was written by Rob Walker on January 30, 2010

Comments Off on “Digital Nation”

Well, is it?

The Significant Objects project has conclusively demonstrated that narrative adds measurable value to objects.

What does this imply about the objects themselves, and whoever created and produced them? Something I hear often from assorted gurus on design, marketing, and the like, is that consumers value the story of an object in the sense of knowing how that object was made, or designed. Did a recognized Design Genius dream it up? Is there footage of the whiteboard meetings where the genius insight was arrived at? Or: Was the object crafted by hand? Perhaps knowing more about the crafter’s skill-acquisition history, or personal ideology, adds valuable narrative.

Yet the Significant Objects project added measurable value even while explicitly ignoring such matters. Every Significant Object carries two narratives, but neither has anything to do with the kinds of stories just suggested. Instead there is the narrative invented by the writer who has agreed to create a story about whatever doodad is for sale; and, in addition, there is the story of the project itself. Probably both of these narratives add value to some extent, with specifics varying from buyer to buyer. But while most of the objects sold over the course of the project have been mass-produced, the intent of whoever designed them, whoever marketed them, and why, and how, is flagrantly disregarded, replaced with pure fiction. Arguably, Significant Objects obliterates designer/producer intent.

Still, whatever the fate of that intent, its results remain in the form of thing itself. Clearly some item sold by Significant Objects have been more intrinsically appealing than others, and it must be conceded that however much our writers’ stories increased the value of an object in the open market, the aesthetics of the object must figure in somehow.

Which brings me to a recent Significant Object: the Mystery Object, with story by Ben Greenman. In this instance, not only is the designer’s intent ignored, not only is the material backstory disregarded, the object itself is not present.

What we have is Ben Greenman’s narrative about the object, and perhaps the narrative of Significant Objects as a project — to which the addition of a non-present object of course adds yet another pleasing plot twist. By eliminating the object itself from the equation until after the bidding has concluded, this auction sells invented Significance in its purest, most uncut form yet.

In a sense, this makes the Mystery Object unique even among the project’s already-singular series of offerings; as a result, it may be the most valuable object yet, not despite its absence from the scene until the moment that value is determined, but because of that absence. Who wouldn‘t want to own such a thing — whatever it is?

Bidding stands at $28.50.

UPDATE: It sold for $103.50. That’s pretty Significant, don’t you agree? Details here.

While the use of tools by animals is unusual, Neil MacGregor points out in the second episode of A History of The World in 100 Objects, it’s not unique to humans: apes use objects, too, for example. The difference is that humans “make tools before we need them” and, more to the point, “we keep them,” for repeated use. The 1.8-million-year-old Olduvai chopping tool, then, suggests the dawning of a “relationship between humans and the things they create which is both a love affair, and a dependency. From this point on, we can’t survive without the things we make.”

In this instance, the chopping tool could be used to get at the meat and marrow of an animal that the actual predator who killed it (a lion, say) couldn’t. So here we have the birth of use-value — and, perhaps, the birth of design. This chopping tool shows humans becoming “distinctly smarter,” and considering “how to make things better,” MacGregor says. Interestingly, though, he also maintains that instead of the half-dozen or more chippings that sharpened this rock into a tool, the job could have been done in maybe two chippings: “Those chips tell us that right from the beginning, we, unlike other animals, have wanted to make things more complicated than they need to be.” Evidently, then, the dawn of design coincides with the dawn of … overdesign.

This notion comes up again in the series’ third episode, concerning another discovery from Tanzania’s Olduvai gorge: a handaxe. This is believed to be 1.2 million years old, and reflects a good deal more skill, forethought, and imagination on the part of its maker – the sort of “focused, planned creativity,” as MacGregor puts it, that marks modern humans.

James Dyson, however, is not impressed. Read more

For sale right now on eBay: “A Tool To Deceive And Slaughter,” described as “a work of art … which consists of a black box that places itself for sale on the auction website ‘eBay’ (the “Auction Venue”) every seven (7) days. The Artwork consists of the combination of the black box or cube, the electronics contained therein, and the concept that such a physical object ‘sells itself’ every week.” The artist is Caleb Larsen.

Before you bid, you have to agree to terms (see the listing) which basically boil down to the imperative that you must let the object go back on sale on eBay, a week after your winning bid. If it sells for more than you paid for it, you pay the artist a 15% commission on your profit. If it doesn’t sell, you can keep it — but it will try again in a week. Basically you can the thing for as long as it doesn’t appreciate in value. (“Any failure to follow these terms without prior consent of Artist will forfeit the status of the Artwork as a legitimate work of art. The item will no longer be considered a genuine work by the Artist and any value associated with it will be reduced to its value as a material object and not a work of art.”)

Bidding is currently at $4,250.00.

(I learned of this via Metafilter. Reading deep into the comments I find that Murketing.com played an indirect role in the realization of Stephanie Syjuco’s “Temporal Aggregate / Social Configuration (Borrowed Beuys)” piece, which involved recreating a Beuys sculpture with objects she borrowed; evidently one of her lenders read about it here — resulting in a very, very rare moment when I sort of maybe think this site is worthwhile.)

The BBC radio series, A History of The World in 100 Objects has gotten underway, and I’m really into it. It’s written and hosted by the director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor. Each episode lasts about 15 minutes, and the first one makes a brief case for history-via-objects by considering the Mummy of Hornedjitef, from the 3rd century B.C., described as “one of the most impressive mummy cases” in the British Museum. Like other objects this one sends the sort of “signals from the past” that things can carry. Since it arrived at the museum in 1835, scholars have translated the hieroglyphics and learned about the society the object came from, studied the charms and amulets entombed with the deceased to deduce that society’s beliefs about journeys of the afterlife, and examined its physical makeup to extrapolate the trading networks of the age. Such objects keep sending new signals, as scholars figure out how to receive them.

In the second episode MacGregor dials us back to the beginning of his story: a 1.8 million-year-old “stone chopping tool” found in Olduvai Gorge, in Tanzania (by a Ricahrd Leakey expedition, under the auspices of the British Museum). Discovered next to bones, the chopping tool seems to have been shaped to strip meat and break into the bones of killed wildebeests and the like. “A very, very versatile kitchen implement,” MacGregor offers.

Although the series is explicit in telling the story of human history by way of things humans have made, I think a history of humanity told via objects ought to start with the Makapansgat Pebble (below). As you can see, it looks like a face. It was found in what is now South Africa, and is estimated to be about 3 million years old. What’s significant about it is that the experts believe, based on the makeup of the pebble, that the spot where they found it, among ancient bones and whatnot, indicate that some hominid/human ancestor carried the thing several miles, which would make it the oldest known manuport.

Makapansgat Pebble

Why was carried away from its place of origin? Well, obviously we don’t know the precise answer, but clearly it’s not a matter of use-value: The pebble is not functional, it’s not a tool. I once heard Mia Fineman, a Met curator and writer, give a talk in which she brought up the Makapansgat Pebble in the context of pareidolia. Pareidolia basically involves spotting patterns that are basically random and attributing meaning to them — like seeing the Virgin Mary’s face in a grilled-cheese sandwich. Possibly the proto-human believed that there was something supernatural about a pebble that looked like a person. Read more

Here’s an essay I wrote in connection with Rewind Remix Replay: Design, Music & Everyday Experience, an exhibition at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, through May 23, 2010. It’s available over there as well, but only as a PDF. So I figured I’d post it here. It’s a bit of an unusual piece for me, and I’m not certain how well I carried it off, but it was fun to write. I welcome feedback…

SITE AND SOUND:

One Home, Sixteen Objects, and the Things We Listen To Now

Surely the first decade of the 21st century will be remembered as a pivotal time in the history of listening. But it won’t be because of a new genre that burst on the scene, the way rock, rap, punk, even disco, changed the music we listen to. It will be because of the objects and technologies that changed the way we listen. Such transitions always seem abrupt (especially as they’re treated in the popular press) but unfold more gradually for most real-life listeners.

So as the decade wound down, I decided to conduct an inventory of objects and devices for music-listening in my own home. I’m more of a music fan than a gadget fan, which leads me to embrace music-oriented technology faster than any other sort (I owned an iPod before I owned a cell phone). At the same time, I can be slow to chuck old formats and objects just because something new has appeared; possibly the more dated relics of twentieth–century listening technology cluttering my home ought to have been discarded by now. But since analog and digital coexist in this particular environment, it’s an opportunity for a useful one-listener object ethnography. Read more

Every year right about this time I remind people: Please contribute photos taken on MLK Boulevards, Drives, Streets, Avenues, etc., anywhere, to the MLK BLVD Flickr pool, an open-source photojournalism project. Highlights appear on the blog MLK BLVD. The image above, from an MLK parade on MLK in New Orleans.

[For the three of you who read the No Notes blog: This is a cross-post.]

Posted Under:

Uncategorized

This post was written by Rob Walker on January 18, 2010

Comments Off on MLK BLVD

The January 2010 issue of The Believer has an interesting book review — interesting in that the reviewer, Justin Taylor, was prevented from knowing anything about the book: who wrote it, who published it, to what genre it belonged, etc. “Its covers, front matter, and endpages had all been stripped, and the spine blacked out with a Sharpie.”

Toward the end of the review, Taylor addresses the “sensory-deprivation school of reading” he’d just experienced:

Jacket copy does more than simply entice you to buy. It supplies a framework for one’s experience. It is less a movie trailer than a placard on a museum wall, telling you not just how to look at the painting, but what to see there when you do.

I think that’s a very good point. Taylor adds some positive words about being a reader “freed from the tyranny of the preprogrammed response.” That’s an interesting notion, too.

That said, physical books will continue to have covers, front matter, blurbs, and other elements of the “framework” Talyor describes. In my (limited) experience, publishers do think of these things as something like a movie trailer or advertisement. That is, they think about the cover design and title and so on in terms of potential readers: How to attract them, get their attention, hook them, reel them in. Will a shorter subtitle grab more people? What snappy language on the flap is most likely to lead to a sale? Is the cover bold enough to stand out from the pile at Barnes & Noble? Etc.

I wonder how these things might be different if they were created with actual readers in mind: Not the person wandering through the bookstore, but the person who has bought the book and is reading it. Would this affect the look of the book, the nature of the jacket copy, maybe even its title? Would the “framework” have more to do with reinforcing (or even influencing) the reading experience, and less to do with the point -of-sale experience? (To use/abuse Taylor’s terms, if these things were thought of more as a placard in a museum and less as a blaring moving trailer.)

Maybe there would be less difference than I assume. But it might be an interesting experiment or design assignment, to think about how a book would look, and how its jacket copy etc., would read, if it were crafted not for the potential buyer, but for the actual reader.

Where, Larry King asks, is the real flying saucer?

I think that’s the phrase he uses, “flying saucer.” His guest is that guy Richard Heene, the guy at the center of the “balloon boy” thing. I first heard about that “story” by way of some report that it was all a hoax. All America was transfixed by this event, and it was a hoax! That’s what the story said. I had no idea what it was referring to. “Balloon boy”? I guess I was busy at the time.

Anyway so that was weeks ago. And now there’s this Larry King rerun, and I’m not really watching because I’m doing some tedious computer work, and if I understand correctly, this guy, Heene, is on his way to prison. But first he’s stopping by Larry King, to more or less imply that it wasn’t really a hoax; it was a misunderstanding. Or something.

Now he and Larry King are standing in front of what has just been described as replica of the “flying saucer” that this guy claimed his kid got into, and floated off into the ether. Only that didn’t rally happen. And so now he’s going to prison.

So: The police have it. That’s Heene’s answer to the question of where the real flying saucer is. King nods. When is the last time Larry King actually gave a shit about the people he talks to, the stories they tell?

The guy, Heene, is very animated, describing the object that he and King are standing in front of. This is a replica of an object that was briefly believed to be involved in a bizarre incident that in fact did not occur.

For a minute I look at the television set, stop what I’m doing. I’ve not laid eyes on Heene before. He has a very strange haircut. Larry King’s posture isn’t so great. But I guess he’s pretty old.

I have no idea what Heene is talking about. He says he didn’t do anything wrong. He looks wounded.

I should describe the “flying saucer.” It’s a big, silver…. Um…

…. Um, who fucking cares? What difference does it make what it looks like? Is there a prop department at CNN? I guess there must be. What does that suggest about the nature of information distribution, of news, today? What is like to build a prop … for the news? Who is in charge of making sure that the simulacrum of the thing that was at the center of a hoax – of a non-event – is, you know, up to snuff?

Where, Larry King asks, is the real flying saucer?

The answer, obviously, is that there is no real flying saucer.

And, somehow, that fact, that nonfact, is why we are here.

Or maybe it was yesterday. Either way, Buying In: What We Buy and Who We Are

Or maybe it was yesterday. Either way, Buying In: What We Buy and Who We Are is now out in paper. It has a yellow cover. And a shorter subtitle. I made a couple of corrections of typos in the original book, but otherwise it’s the same, only cheaper. And with a yellow cover and… etc.

is now out in paper. It has a yellow cover. And a shorter subtitle. I made a couple of corrections of typos in the original book, but otherwise it’s the same, only cheaper. And with a yellow cover and… etc.

If you’re an educator who might want to assign the book, I might be able to get you a freebie to evaluate. Students seem to respond to it well, and I had great experiences doing Skype visits to classes in connection with the book last year. Contact is murketing@robwalker.net if you’re interested.

I am doing that, this month. If you miss the old linkpiles, maybe you’ll like what I contribute over there, to Coudal’s Fresh Signals feed.

Posted Under:

rw

This post was written by Rob Walker on January 4, 2010

Comments Off on Guest-editing on Coudal.com

As noted.

So, no column again today because, as noted last week, Consumed is on hiatus until late March. I’m not going to announce this every week obviously, but I got some questions about this and the short answer is there’s nothing dramatic going on, good or bad. I’ve just been doing the column for six years now, and asked for a little break to work on some other things. My delightful editors were kind enough to let me do that. (And after all I’m a freelancer, so it’s not like it’s costing them anything if I produce less for them for a little while.) So that’s pretty much the whole story! No worries, no secrets.

Happy new year…

Posted Under:

rw

This post was written by Rob Walker on January 3, 2010

Comments Off on Re: Hiatus

Well it’s January 1 and thus time once more to look back at my personal listening data to see if it can help me name my 10 favorite songs of 2009. (I have previously conducted this empirical-subjective exercise for 2007 and 2008.)

Here’s the Top Ten, followed by the number crunching.

[table id=1 /]

As in the past, I start out by seeing which songs I played most often, per iTunes data. And I cross-match that with my one-out-of-five-stars rating, and tweak accordingly. “Out At Sea” by Heartless Bastards was my most-played song of 2009 that was also released in 2009, according to my iTunes. This lines up with the subjective view: It probably is my favorite song of the year, it’s awesome, and perhaps if it ends up in a car commercial or whatever it’ll get the respect it deserves.

“Bumpo” was probably my favorite thing from Nomo’s record, but I pared away some others that I listened to almost as much. The next few tunes I’d say the playcount lines up with subjective liking. “Le Petit Sauvage” at number 6 is a bit of a cheat: I seem to like it more than I’ve played it.

The next several tunes all need some kind of comment. I’m late to the game on “How You Like Me Now,” by The Heavy, which I gather became well-known early in the year by way of a TV show or something; I only heard it pretty recently, and I think the low play count reflects the fact that I haven’t had it that long. A similar issue (recent-ish release) made me cheat “Bad Romance” past other stuff I’ve played more often. The Bran Flakes put out an interesting record, but I had to exercise subjectivity to pick “Stumble Out of Bed” as the best track; I actually listened to “Van Pop” more frequently (and that’s also really good). (In retrospect, however, I wish I’d just gotten a few Bran Flakes songs, not the whole album.)

Props to Disquiet and its regular postings of free, legal downloads, for being the source of two of my faves: Shoebomber’s “Le Petit Sauvage,” and the Grassy Knoll re-invention of Junior Kimbrough, “Done Got Old.”

Missing the top ten by a narrow enough margin that subjectivity easily could have put them over the top if I’d been in a slightly different mood. “Good Eye,” by Bruce Springsteen, because although the record isn’t great, this song is; “Crystalized” by The xx (I first heard it via Popcop); “It’s a Rainbow (Blame Me),” by Lisa Germano, which is from The Believer‘s music issue; “Space City,” by Booker T, because as much as I listened to his pleasing 2009 album, I think the whole beats the parts; “Las Hadas” by Juan Son (I heard it via DJ/Rupture’s site); and “The More I Do,” by The Field.

I also took a look at some data collected by LastFM, and another site I learned of this year (via Music Machinery), called Normalisr, which dips into your LastFM data and tracks your listening by time, instead of by number of plays. More, including my favorite non-2009 songs of 2009, after the jump. Read more

Posted Under:

Music

This post was written by Rob Walker on January 1, 2010

Comments (7)

"

"

Kim Fellner's book

Kim Fellner's book  A

A